How Verizon Wireless Is Tracking You All Around the Web

(Rob Pegoraro/Yahoo Tech)

When Web publishers first started saving information about their visitors in tiny text files called “cookies,” much of the Internet freaked out: “You mean there’s some little program on my computer that follows me around the Internet?”

No, people like me would explain. Cookies don’t do anything on their own and can be read only by whatever site created them.

Or so we thought. What if the one company that stays with you wherever you go on the Internet — that is, your Internet provider — started inserting cookies in your webpages and could track your online habits for marketing purposes?

Those are the basics of the outrage over the discovery that Verizon Wireless is tagging most of its subscribers’ Internet traffic with individual identifiers as part of an advertising initiative.

As the Electronic Frontier Foundation’s Jacob Hoffman-Andrews wrote Monday, this Verizon tracking “effectively reinvents the cookie, but does so in a way that is shockingly insecure and dangerous to your privacy.”

And you can’t turn it off.

What Verizon does to your data

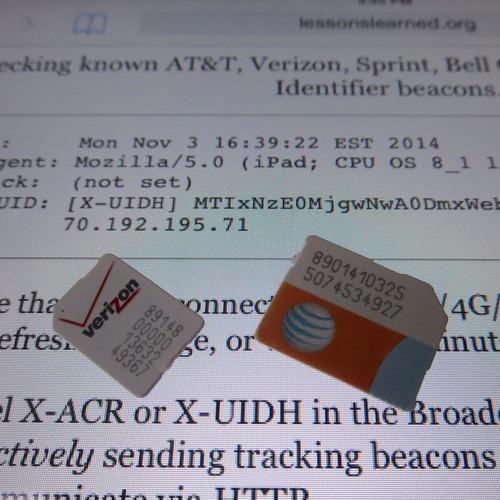

How can Verizon do this? When it relays an address request from a device on its network (your phone, for example) to a website you’re visiting, it adds a “Unique Identifier Header,” or “UIDH,” that ties the request to your account. For example, a Verizon LTE hotspot I’m testing has each request for a webpage silently stamped with 60 characters of gobbledygook beginning with “MTIxNzE0.”

You can’t see this on your smartphone or tablet, but the website you visit can read that UIDH and know you by it, even if you’re browsing in incognito mode.

You can consult specialized test pages that check for this tracking — for example, security researcher Kenneth White’s lessonslearned.org/sniff. The tech-policy lobby Access has since posted amibeingtracked.com, which goes easier on the jargon but takes an extra click.

Only sites that encrypt the connection between them and your browser can thwart this “header injection.” That includes most email, social media, and financial sites (as well as Yahoo Tech, so your emoji fascination is safe from Verizon’s scrutiny). But if the site you’re visiting doesn’t put that little lock icon in the browser toolbar, and you’re accessing it over Verizon’s wireless network, then it’s tracking you.

In a frequently asked questions page, Verizon says this system lets “select ad technology partners” target ads to “groups of customers … based on demographic and interest based information.”

You can opt out of that demographic and interest-based targeting by logging into your account’s privacy settings on the Web, using the My Verizon app on some phones, or by calling 866-211-0874. But note that this doesn’t stop Verizon from inserting the identifying headers into your Web traffic, it just tells it to not use the data.

Which, as White emphasized in an email, is “broadcast to every site and app service that users visit,” except encrypted connections.

Verizon says that’s not a risk because its headers change “frequently.” But it won’t say exactly how often they change or by how much.

And as Hoffman-Andrews (mentioned earlier here as a developer of the BlockTogether anti-harassment Twitter app) wrote in that EFF post, it’s trivial to link one header ID to its replacement by using other Web-tracking technologies like cookies.

Everybody else does not do the same thing

White’s site soon revealed that AT&T was also injecting these headers. But AT&T has implemented what it describes as a test of a possible advertising service in a more polite manner.

Although it’s not obvious from that company’s privacy-policy page, you can click a button at an opt-out page (mobileoptout.att.com), and then confirm at White and Access’ test pages that you no longer have tracking headers stapled to your traffic.

Sprint and T-Mobile, meanwhile, don’t engage in this tracking at all — even though they make a lot less money than AT&T or Verizon. (The latter happens to lead the industry in its proportion of over-$100-monthly subscribers.)

Verizon’s FAQ stresses that advertisers don’t actually see who its customers are, because it anonymizes the data provided through its “Relevant Mobile Advertising” and “Verizon Selects” programs.

In the abstract, that’s not too different from how Facebook lets its advertisers target its members by location, interest, and other criteria less specific than name and address. But Facebook is free, and its members expect to be advertised to. People pay to use Verizon and do not expect to have their behavior sold.

Further, you can tell an enormous amount about theoretically anonymized people if you can see almost everything they read online. Think about how quickly researchers could identify the people whose anonymized search traffic was released by AOL as part of a study in 2006; the same principle applies here.

Just because you can doesn’t mean you should

In one way the growth of the Internet has paralleled your standard mad-scientist movie: First somebody figures out a way to do something really interesting (in this case, track users more closely online), and only later do people start to ask, “Wait … is this a good idea?” A public discussion of the possible downside takes still longer.

Likewise, the architects of these mad plans never think they’ll get caught, until they inevitably do. From ISPs toying with using “deep packet inspection” to the National Security Agency’s “collect everything and sort it out later” overreach, we have seen this movie before.

With Verizon, though, one thing is different. The wireless industry has far more effective competition than residential broadband or the federal government. You can choose to take your business elsewhere if you don’t approve of Verizon’s conduct.

Or Verizon could recognize its untenable position and give its paying customers an easy way to opt out of this tracking. It shouldn’t be that hard … right?

No comments:

Post a Comment